Yesterday, November 9, marked two years since my father passed away, very suddenly with no warning, leaving a trail of shocked and broken hearts behind. We were very close, and his death was traumatic in a way that is difficult for me to adequately describe in words. Those of you who know me may recall how long it took me to return to something that looked like normal. And those of you who knew my father will surely understand why losing him is was so devastating.

When I was helping my mother to clean out his home office, I found among his things a letter I had written when I was perhaps about eight or nine years old. It was a list of the reasons why I loved him. Here's what it said.

Why I Like Men Like Daddy

1. They never give a definite yes or no.

2. They don't get mad easily.

3. They are very easy to talk to.

4. They take time for their kids every Saturday.

5. If their kids go swimming, they are very careful.

6. They are not too comical but comical enough.

I could write a much longer, more eloquent list now, but I actually like this one a lot. It works quite like that famous one about

Everything I Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten ... it says all the important stuff in just a handful of words. My father had a smile for everyone, a warm hug for anyone who needed it, a joke that made you laugh because it was so lame, and the heart of a child who found joy in literally everything he did. He knew how much he was loved, and that makes me incredibly happy.

My Algeria book is taking a bit longer than expected to get through, so I thought I'd write about books that make me think of my Dad. When I was a little girl, I felt so proud of my Dad ... because he could recite

The Cat in the Hat by heart! I assume he acquired that particular talent by reading it over and over and over to me and my sister at bedtime, which was his responsibility and one he took very seriously. Each evening after dinner, he was in charge of bathing, teeth brushing, the saying of prayers, stories, and tucking us in snugly and lovingly. We read a lot of Dr. Seuss. And

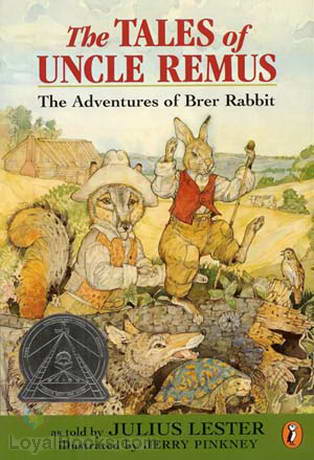

Uncle Remus, with Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox, and Br'er Bear. Long after I was grown, my father continued to say "Oh pleeeeeease don't throw me in the briar patch!" if there was discussion of something he really, really wanted to do. (This will only make sense to you if you, too, were readers of Uncle Remus.) We had a set of Disney books with all of the childhood favorites, like Cinderella and Snow White and Bambi, and lots and lots of Bible stories. He was always happy to read whatever I brought home from my weekly trek to the library with my mother though. These are wonderful memories from my childhood.

As I got older, we graduated to chapter books, classics like

Heidi, Pippi Longstocking, The Little House on the Prairie and

Charlotte's Web. Eventually, bedtime became something I did on my own ... although I don't think I ever turned out my light without first kissing him good-night and saying, "I love you." Reading, too, became more of a solitary pursuit or something I began to enjoy with my mother more than my Dad, who understandably wasn't interested in Judy Blume or later, Danielle Steel.

Dad never stopped sharing books with me though. On my bookshelves, I still have several books he gave me, each with an inscription about how much he

loved me and why he thought I'd enjoy that particular book. Most of them were about religion, leadership, or poems about daughters. Someone else will have to purge those from my home when I'm long gone; they are far too sentimental for me not to save them.

When I was around 15, Dad's friend,

David Poyer, published a book called

The Return of Philo T. McGiffin. I was absolutely thrilled to receive a copy with my first-ever, personalized dedication, handwritten in the front of the book by the author, ... who spelled my name correctly and everything! The legend behind this book, at least as far as my family is concerned, is that while preparing to write it, Poyer created a huge map of the fictional setting of the story and allowed his friends to name different areas on the map. To my father's eternal delight, he selected a space on the map and christened it as Bates' Bog. We scoured

The Return of Philo T. McGiffin, to no avail ... nothing happened in Bates' Bog in that book. I've always wondered if it showed up in any of the others Poyer wrote.

As a Captain in the U.S. Naval Reserve, Dad loved naval fiction, and as a deeply spiritual man with a strong Christian faith, he loved inspirational books by Charles Swindoll and other similar writers. And then there was the political side of him. He was a passionate Democrat who loved Bill and Hillary Clinton. He read many left-leaning books about politics, social justice, and community. From his shelves, I have kept

It Takes a Village, by Hillary Clinton, and

The Working Poor, by David Shipler, as I recall we had some really outstanding conversations about these two.

How I wish I could have one more conversation with my father. I know just what I would say: I miss you, I love you, and I am so, so grateful for every moment we shared. What makes the loss of him bearable is knowing how incredibly lucky I was to be his daughter. I am reminded of a passage from the storybook he read most often to my children, The Velveteen Rabbit.

"What is REAL?" the Velveteen Rabbit asked the Skin Horse one day. "Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?"

"What is REAL?" the Velveteen Rabbit asked the Skin Horse one day. "Does it mean having things that buzz inside you and a stick-out handle?"

"Real isn't how you are made," said the Skin Horse. "It's a thing that happens to you. When a child loves you for a long, long time, not just to play with, but REALLY loves you, then you become Real."

"Does it hurt?" asked the Velveteen Rabbit .

"Sometimes," said the Skin Horse, for he was always truthful. "When you are Real you don't mind being hurt."

"It doesn't happen all at once," said the Skin Horse. "You become. It takes a long time. That's why it doesn't happen often to people who break easily, or have sharp edges, or who have to be carefully kept.

Generally, by the time you are Real, most of your hair has been loved off, and your eyes drop out and you get loose in your joints and very shabby. But these things don't matter at all, because once you are Real you can't be ugly, except to people who don't understand. But once you are Real you can't become unreal again. It lasts for always."

Thank you, Dad, for making me Real.